You take it for granted.

You don’t know you do, but you do. Knowing where you came from, how you came to be in the world, how you came to have that laugh or those eyes. Maybe it doesn’t seem like a big deal to you, you don’t care. But it’s the luxury of not caring about something you have and can discard. For me, and lots of people like me, not knowing how or why you got here — it hurts. Without a backstory, a first act or a prologue, you feel just plopped down in the universe with no tether, no anchor, and no map or North Star to find your way.

It’s lonely being adopted, because . Everyone else knows where they came from and dismisses it as unimportant. You alone care, and you’re not only alone in caring, but sometimes punished for it. One day when I was about 13 I was at the eye doctor. He asked if there was a history of glaucoma in the family, and my mother piped up and started to say there was. I added that it actually wasn’t relevant for my medical history since I was adopted. I didn’t make a big deal about it, I just understood why he was asking. Later, when we got out to the parking lot my mother slapped my face, snarling, “Why do you always have to remember that? I don’t, why do you have to?” Now as an adult I can feel for my poor mother’s fragility around the issue. Still, I wish back then someone could have been sensitive to mine.

I’ve always longed to know how I got here, and the day before Thanksgiving last year, I finally found out:

Many improbable and hare-brained things are hatched in our nation’s capital, and turns out I was one of them.

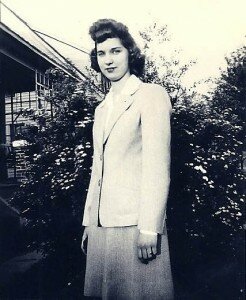

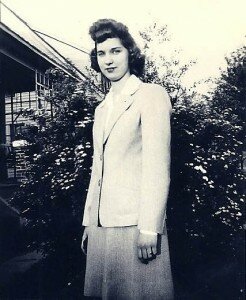

A half century ago, a Washington DC bigwig was driving his secretary home late one night. As wigs go he was one of the biggest (and his brother was even a bigger wig). The secretary was an average woman who’d left home on the farm at 16 and come to town 2 decades earlier with the influx of workers needed when World War II erupted. The two had a professional relationship, and if anything the secretary was irritated by the wigs’ size and its accompanying know-it-all-ness. After all, she’d been in government 20 years and she though this Phi Beta Kappa upstart was a little too big for his britches.

It’s hard to get a handle on just what happened that night. Only a few things are certain: Doris had sex for the second time in her life; she had sex for the first and only time her boss; and 9 months later the world got 10 more fingers and 10 more toes foisted upon it.

Eight months earlier a doctor had given poor Doris the bad news, but told her he could get the problem fixed. She would have gone that route, but she’d heard of girls dying in back-alley abortions and the prospect of bleeding to death on some dirty mattress somewhere was too daunting. She couldn’t get married because she “didn’t like any of the fellas I was going with enough to get married.”

Doris told the big wig boss about her situation but other than a check he cut for $300 (“I don’t know what that was supposed to be for”) it seems the matter was closed. So about 3 months later she got on a bus to Miami Beach – she’d always wanted to see Miami Beach – and when she arrived she got a room in a small inexpensive hotel and began leafing through the phone book to find a doctor. So there she waited for the inevitable — me.

I was born April 17th. The next day Doris sent in her letter of resignation. A woman she’d met in the hospital lobby 2 days earlier brought her a baby present; Doris doesn’t remember what she did with it.

She went back to Washington DC to get pack some things. She says the big wig contacted her saying he would marry her and they’d raise the baby together, to which she replied, “Too late, Sonny Jim.” (When I asked Doris how he might marry her when he was already married, she shrugged.) She moved back to Missouri.

A year later “Mr. Wig” was giving a speech in Chicago and contacted Doris and asked to take her for dinner. She didn’t want to go –“I didn’t like his personality much” – but she relented because “I wanted to hear his excuses.” (I asked what she meant by that but she couldn’t elaborate.)

I asked what was said about, well, me, at that awkward dinner. “Neither one of us brought it up,” she explained.

Fast-forward a half a century later — Doris is eighty-eight years old and living in a sort of nursing home in Florida. She never married, never had any other children, but she hears from her nieces and nephews every once in awhile. The day before Thanksgiving poor Doris gets a phone call. “Hello, my name is Sarah,” says the tentative voice on the line, “I was born April 17th 1962 in Miami Beach…may I speak to you for a few minutes?” A long pause. “Um, do you understand who I am?” asks the voice. Another even longer pause. “Yes,” says Doris in her high, child-like voice. Continue reading I Finally Found My Mother, Myself, and A Lot More